clamanti cutis est summos direpta per artus,

nec quicquam nisi vulnus erat; cruor undique manat,

detectique patent nervi, trepidaeque sine ulla

pelle micant venae; salientia viscera possis

et perlucentes numerare in pectore fibras.

Ovidius, Metamorphoses VI, 387-391

As he screams, the skin is flayed from the surface of his body, no part is untouched. Blood flows everywhere, the exposed sinews are visible, and the trembling veins quiver, without skin to hide them:

you can number the internal organs, and the fibres of the lungs, clearly visible in his chest.

Translated by A. S. Kline

Apollo flaying Marsyas.

This scene looks very much like a performance.

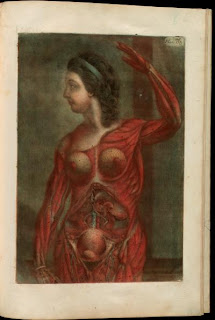

ANATOMY

One of the main inspirations for many od our performances have been the old anatomy plates:

Odoardo Fialetti, De humani corporis fabrica, 1631

Juan Valverde de Amusco, Anatomia del Corpo Humano, 1559

Etienne de La Rivière, De dissectione partium corporis humani, 1545

Juan Valverde de Amusco, Anatomia del Corpo Humano, 1559

Etienne de La Rivière, De dissectione partium corporis humani, 1545

Jacques Gautier d'Agoty, Myologie complette, 1746

FLAYING

Flaying is the removal of skin from the body. Generally, an attempt is made to keep the removed portion of skin intact.

There were differents versions of flaying.

In one version of the flaying torture, the victim's arms were tied to a pole above his head while his feet were tied below. His body was now completely exposed and the torturer, with the help of a small knife, peeled off the victim's skin slowly. In most cases, the torturer peeled off his facial skin first, slowly working his way down to the victim's feet. Most victims died before the torturer even reached their waist.

In another version, the victim was exposed to the sun until his skin reddened. This was followed by the torturer peeling off his flesh with the same method described above.

In yet another version, the victim was submerged into boiling water and was taken out after a few minutes. He was slowly flayed.

.............................................................................

in our performance flaying has nothing to do with torture, it's more related to skin shedding. But still, we find the images of flayed Marsyas and St Bartholomew very inspiring.

In Greek mythology, Marsyas, a satyr, was flayed alive for daring to challenge Apollo.

Rotterdam Tile in Wilstermarsch-Zimmer, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg

Apollo, Marsyas, and the Judgment of Midas, Melchior Meier, 1582

.............................................................................

Bartholomew was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus.

Tradition holds that he was flayed before being crucified.

Marco d'Agrate, 1562 (Duomo di Milano)

Pierre Le Gros, 1708-18 (Basilica San Giovanni in Laterano)

Matteo di Giovanni, ~1480

Michelangelo, Last Judgment, 1536-1541 (Sistine Chapel)

.............................................................................

Transi de René de Chalon, Ligier Richier, 1547

This figure, displayed in the Saint-Étienne church in the city Bar-le-Duc in France, once held the heart of its subject René de Chalon, Prince of Orange in its raised hand, like a reliquary. The prince died at age 25 in battle following which, depending on which story you believe, either he or his widow requested that Chalon portray him in his tomb figure as "not a standard figure but a life-size skeleton with strips of dried skin flapping over a hollow carcass, whose right hand clutches at the empty rib cage while the left hand holds high his heart in a grand gesture" (Medrano-Cabral) set against a backdrop representing his earthly riches. Alas, the sculpture no longer contains Chalon's heart; it is rumored to have gone missing sometime around the French revolution.

SHEDDING

In biology, moulting, also known as sloughing, shedding, or for some species, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often but not always an outer layer or covering), either at specific times of year, or at specific points in its life-cycle.

The most familiar example of moulting in reptiles is when snakes "shed their skin". This is usually achieved by the snake rubbing its head against a hard object, such as a rock (or between two rocks) or piece of wood, causing the already stretched skin to split. At this point, the snake continues to rub its skin on objects, causing the end nearest the head to peel back on itself, until the snake is able to crawl out of its skin, effectively turning the moulted skin inside-out. The snake's skin is often left in one piece after the moulting process. Conversely, the skin of lizards generally falls off in pieces.

A gecko sheds its skin regularly. If the lizard takes on a dull, cloudy almost ghostly appearance, this indicates that the shedding process has begun. Its skin peels off the body in pieces, which the gecko tugs and pulls off and then consumes.